I have not been alone in musing about the iPad for the past few weeks. Just what is it? What will it do? Why would I want one? What is it for? Today I stumbled upon an answer. The iPad is not a device to read electronic books, the iPad will help us invent electronic books. More “below the fold”…

This insight gelled for me as I read a post by William Rankin at Open Culture aboutThe iPad and Information’s Third Age. Rankin describes the first two ages of information as pre-Gutenberg (one on one, books cost a lifetime) and post-Gutenberg (widespread access accompanied by symbolic complexity). Now the network has begun to unite a sliced up world, it has begun to lower the symbolic barriers. A third information age is emerging.

I would look at the same three periods, but through a slightly different lens, that of the author. Pre-Gutenberg authors had one on one relationships with their learners. There were a few exceptions, because history and scripture were passed along from one to many, but the costs of such transmission were tremendous and so the opportunity to become a voice in that timeless conversation was severely limited.

We’ve all lived in the post-Gutenberg world. For us the opportunities of authorship have been much more available. A person could own a printing press, or work with a publisher, and reasonably expect to reach many learners. Libraries arose to stash away this wisdom of the ages, universities arose to organize the production of these works and their utilization, publishers arose to facilitate access to the means of distribution. The limits of the physical format that allowed mass distribution also shackled authors to a linear form, to words in a row on one page after another.

Today we are in the midst of a birth of something new, though. Something that goes beyond the one to many post-Gutenberg model. This is a transformation of media. It began with the rebirth of an oral tradition in the last century, a means of mass distribution of something beyond words on a page. Radio and television brought voice and image back to the conversation. But the promise of this new media has really become evident with the emergence of the computer arts and digital media. This has both made the production and distribution of audio and video content accessible to a much wider set of authors and transplanted the written word from sequential pages to a web of related resources that one moves through with clicks and taps. We hardly know what this new media is yet, but it emerges around us nonetheless.

This context brings me back to the iPad, a device we have been anticipating for over forty years. This is a device that makes this new media intimate and mobile enough to become part of our daily lives. The iPad is not about allowing us to read the works of the post-Gutenberg world in electronic form (an “e-book reader”) though it will do that very well. Rather the iPad is about the invention of the third information age. Now that we have text, audio, video, and computing arts all available to the author, what will we make of it? We already have hints that part of this transformation will be from a one to many conversation that is linear through time to a many to many conversation that informs the author as much as any of their learners. In fact, the author becomes the facilitator of a learning experience that everyone shares.

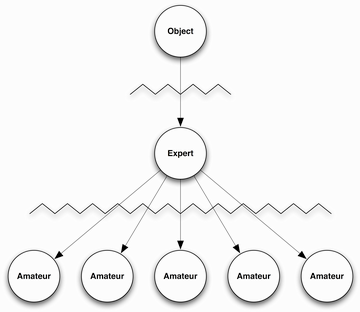

Mary often cites Parker Palmer when she discusses teaching and learning. She shows two diagrams, derived from The Courage to Teach. They both depict the relationship of teacher to learner to their subject. One would look familiar to anyone who went to school and attended a lecture:

This “instrumental knowing” model would also be familiar to authors in the post-Gutenberg age. The author researches a topic, writes a book, and lots of readers, amateurs, lap it up and learn from it. We hope. The second model is a bit more dynamic.

In fact, some wonder where the teacher (or author) has gone in this model. Mary likes to say that the teacher has become a facilitator of each learner’s relationship to the subject. Everyone learns from one another, the teacher helps ensure the process works. This “relational knowing” model also serves to illustrate what I think may be happening to books as they are reborn in our new media landscape. The author becomes a facilitator of a community conversing around at topic. The author inspires this conversation by getting it rolling, but the tools of computing arts and digital media also allow the readers to talk back, to teach, to author. Palmer puts it this way:

It is out commitment to the conversation itself, our willingness to put forward our observations and interpretations for testing by the community and to return the favor to others. To be in the truth, we must know how to observe and reflect and speak and listen, with passion and with discipline, in the circle gathered around a given subject.

The iPad, I realize today, is at the heart of this transformation. It is a device with the power to bring relational knowing to what we have known as “books.” Apple talks about the iBookstore and is working with publishers to line up iBooks to go on those virtual shelves. Those iBooks will be cool, no doubt, but they will simply be new versions of post-Gutenberg texts. The real revolution is in the App Store. As authors and publishers realize that on the iPad there is no reason at all to stick to the post-Gutenberg rules. A “text” can be anything, it can come alive in new ways, and it can incorporate the voice of its readers as well as that of the author.

The iPad will lead to the invention of the e-book. We have not seen it yet (though there have been hints), we hardly know what we are looking for, but I am sure it is coming. I wonder how many publishers will catch on, and how many authors are ready for the challenge.